Rabia Mustafa

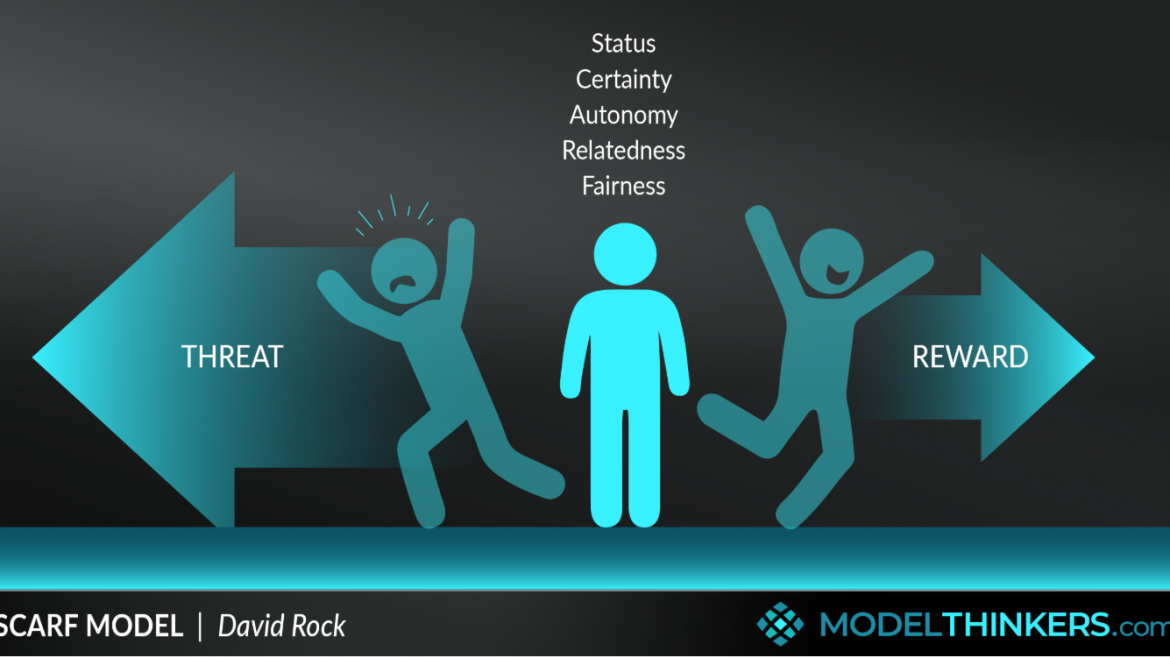

The SCARF model, developed by David Rock, is a brain-based framework that identifies five domains of human social experience that influence behaviour in the workplace and beyond. These domains impact our reactions to threats and rewards, shaping engagement, collaboration, and performance.

SCARF stands for:

- Status: Our relative importance to others or what we like we should be perceived by others. The brain perceives a reduction in status as a threat and an increase as a reward. Even subtle changes can trigger strong emotional reactions. (means we dislike if someone looks down upon us, and like when we get appreciation).

- Certainty: The ability to predict the future. The brain craves clarity and predictability; uncertainty generates a threat response. Clear goals, expectations, and communication reduce this threat. (We like clarity in life and being able to predict what is happening around us; something that changes happens, and it seems like danger to us.)

- Autonomy: A sense of control over events. When people feel they have choices and influence, they experience a reward state. A lack of autonomy leads to stress and disengagement. (Everyone likes to be in a control situation where they can influence or mark their identity).

- Relatedness: Feeling safe with others; a sense of connection and belonging. Social exclusion activates the same brain areas as physical pain. Building trust and inclusion supports a reward state. (It is a sense of belonging to a group where people like to associate themselves. We like that we are surrounded by our own ‘clan’ or ‘group’ or ‘association’; it gives confidence and trust.)

- Fairness: Perception of fair exchanges between people. Unfairness evokes a strong threat response: transparency and consistent treatment foster perceptions of fairness. (We do not like it if someone becomes unfair to us; rather, we like that we are treated equally and fairly, and that should be consistent. If this consistency changes, we feel threatened.)

Key Insights:

- The brain processes social threats and rewards with the same intensity as physical ones.

- Leaders and organisations can use the SCARF model to improve motivation, engagement, collaboration, and change management by minimising threats and maximising rewards across these five domains.

- Recognising and addressing SCARF triggers can transform how people interact in teams, make decisions, and adapt to change.

Using the SCARF Model in Mediation

During mediation, emotions often run high, and the success of the process depends not only on facts and negotiations but also on how safe, respected, and understood the parties feel. The SCARF model, Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness, can guide the mediator in creating a psychologically safe environment that fosters dialogue and resolution.

- Status

Mediation should maintain the dignity of both parties. The mediator must avoid any language or behavior that implies one party is superior. By acknowledging each person’s perspective and giving equal opportunity to speak, the mediator helps preserve a sense of respect and status for all involved. (if parties feel secure about their self, they would be okay to communicate and move further.)

- Certainty

The mediator should clearly explain the mediation process, its steps, possible outcomes, and the roles of each participant. Predictability reduces anxiety. Reminding parties of the voluntary nature of mediation and the structure of the sessions gives them a sense of clarity and confidence. (Parties must know what they are going to do.)

- Autonomy

Allowing the parties to make their own decisions regarding the resolution enhances their sense of control. The mediator should avoid imposing solutions and instead support the parties in co-creating agreements. Autonomy helps reduce resistance and increases commitment to outcomes.

- Relatedness

Establishing trust is vital. The mediator should foster a non-judgmental and empathetic environment, showing neutrality and encouraging respectful listening. When parties feel safe and understood, they are more willing to cooperate and move toward resolution.

- Fairness

Ensuring that the process is transparent and unbiased is key. The mediator must treat both sides equally, giving them equal time and attention. Agreements should be mutually beneficial and documented clearly. Fairness in mediation builds trust and supports long-term compliance. (This is essential that parties are treated fairly and they have trust in the mediator that he or she would be fair in facilitating the process and outcome.)

By integrating the SCARF model, mediators can better manage emotional dynamics, improve communication, and increase the likelihood of a meaningful and lasting resolution, even if full agreement isn’t reached. This model reminds us that beneath the surface of any conflict lie basic human needs that, when acknowledged and respected, can open pathways to peace.

The writer is Senior Research Fellow at the School for Law and Development